A large and growing share of Americans are obese. Health experts are calling it an epidemic, and costs to the nation’s medical system are huge. Obesity‐related conditions include heart disease, stroke, diabetes, asthma, joint problems, some cancers, and other ailments.

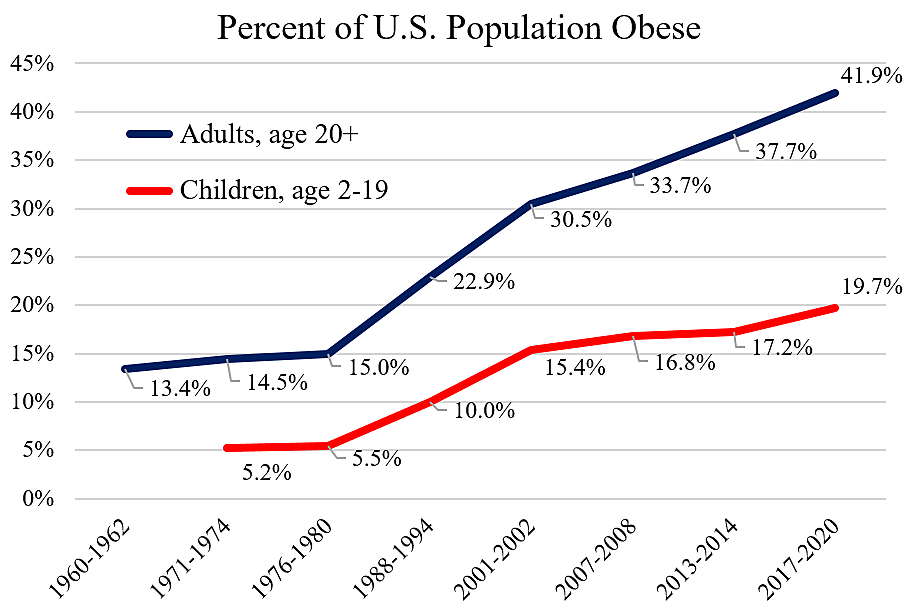

The chart below shows the share of U.S. adults who are obese has risen from 15 percent in late 1970s to 42 percent today. The share of children who are obese has risen from six percent in the late 1970s to 20 percent today.

Obesity for adults means a BMI of 30 or more. So an average‐height man of 5’ 9” is obese if he weighs more than 203 pounds. Obesity is a higher weight category than overweight, which is BMI 25 to 30.

The rise in obesity may be viewed as resulting from individual choices, but it also raises many public policy issues. One of my concerns is: Are some government programs feeding the problem and making it worse?

This concern should be on the front burner this year because Congress is scheduled to reauthorize the “farm bill.” The farm bill will likely include more than $30 billion a year for farm subsidies and more than $120 billion a year for food stamps, also called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Both programs are run by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Health experts point to both farm subsidies and food stamps for contributing to obesity, but there are disagreements given the complexity of nutrition issues. At least, policymakers should investigate the obesity issues before taxpayers are forced to swallow yet another bloated farm bill.

SNAP

The “N” in SNAP is for nutrition, but that is wishful thinking. Recipients can spend SNAP benefits on virtually any food item in grocery stores or local markets except alcohol, hot items, or items for on‐premise consumption. In a 2016 study, the USDA found that 23 percent of SNAP spending is on sweetened drinks, desserts, salty snacks, candy, and sugar. Let’s call that junk food. Thus, the same government that spends billions to encourage Americans to eat healthy is simultaneously spending roughly $25 billion a year or more supporting junk food.

Poverty and health advocacy groups often ignore this reality because they don’t want to undermine support for programs and spending. This annual 92‐page report on obesity, for example, proposes an endless array of new regulations on the private sector and new subsidies to improve nutrition, but it is silent on the $25 billion junk food subsidy. The report proposes new taxes on soft drinks, but fails to mention that the single largest commodity purchased in SNAP is soft drinks.

A recent 31‐page report on SNAP and health by liberal group CBPP says “SNAP is an effective program that helps millions of people in the U.S. access a nutritious diet.” The report uses the word “nutrition” dozens of times, but does not inform readers about the $25 billion junk food problem.

The Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) noted recently that SNAP participants “have lower total Healthy Eating Index (HEI) scores than nonparticipants with both the same and higher income levels.” Similarly, this study found, “Children participating in SNAP were more likely to have elevated disease risk and consume more sugar‐sweetened beverages (SSBs), more high‐fat dairy, and more processed meats than income‐eligible nonparticipants.”

The 2016 USDA study found that SNAP shoppers bought slightly more junk food than non‐SNAP shoppers. For example, 9.25 percent of total purchases by SNAP shoppers were for sweetened beverages such as cola, which compared to 7.1 percent for non‐SNAP shoppers. A 2015 USDA study found that 40 percent of SNAP recipients were obese compared to 32 percent of similar‐income individuals not taking SNAP.

This is a major failure for SNAP, which the statute says is supposed to be “raising levels of nutrition among low‐income households.” To solve the junk‐food problem, BPC proposes an array of new subsidies for people to buy fruits and vegetables. But, instead, why not shrink SNAP to a much smaller program that just subsidizes fruit and vegetable purchases by low‐income households? Ultimately, SNAP should be devolved entirely to the states, but downsizing to a less costly fruit‐and‐veggie program could be a compromise favored by both fiscal conservatives and nutritionists.

Farm Subsidies

Farm subsidies have long raised nutrition concerns, but academic studies come to conflicting conclusions. This study finds, “Government‐issued agricultural subsidies are worsening obesity trends in America.” This study finds, “higher consumption of calories from subsidized food commodities was associated with a greater probability of some cardiometabolic risks.”

This study says that the farm bill influences our health “by effectively subsidizing the production of lower‐cost fats, sugars, and oils that intensify the health‐destroying obesity epidemic.” This study concludes that “a higher consumption of foods derived from subsidized commodities is associated with obesity, abdominal adiposity, and dysglycemia, and further reinforces the potential benefits of aligning agricultural policy with health recommendations.”

However, other researchers argue that subsidies don’t affect consumption much, if at all, because the costs of subsidized crops represent only a fraction of total retail food prices. This study found that “removing US subsidies on grains and oilseeds in the three periods would have caused caloric consumption to decrease minimally.” This study found U.S. farm policies “have generally small and mixed effects on farm commodity prices, which in turn have even smaller and still mixed effects on the relative prices of more‐ and less‐fattening foods.”

Farm subsidy/nutrition issues are hotly debated, and I have not done a detailed research review. If Congress withdrew subsidies from corn, wheat, soybeans, and rice, would U.S. farming shift toward healthier fruits and vegetables? Are the subsidized crops and related oils a cause of obesity, and has the government given Americans bad nutrition advice about these products for decades, as Nina Teicholz argues? Would Americans eat healthier if we repealed farm and food subsidies of all types? These are questions policymakers should be exploring.

Congress should repeal farm subsidies because they distort the economy, harm the environment, and unfairly subsidize high earners. But also, with the growing impact of obesity on society, health concerns are another reason to re‐think passing a huge lobbyist‐driven farm bill in 2023.

Data Notes: the obesity data are from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey results here, here, and here. Surveys have not followed a regular time pattern, so I’ve included years at roughly similar intervals. For the first three time periods, adults are age 20–74.

Departments:

Themes: