Senate Testimony

Mr. Chairman and members of the committee, thank you for inviting me to testify. I will discuss the Trump administration’s efforts to reform the government by improving management efficiencies and cutting programs. The administration’s agenda for reform was laid out in an April memo from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) entitled “Comprehensive Plan for Reforming the Federal Government and Reducing the Federal Civilian Workforce.”1

The OMB memo directs federal agencies to assemble Agency Reform Plans (ARPs), which will become input to the administration’s 2019 budget. Among other requirements, agencies should consider “fundamental scoping questions” to determine whether some activities would be better performed by state and local governments or the private sector.

Spending Reform Is Needed

Without reforms, federal spending as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to grow from 21 percent today to 27 percent by 2040, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline.2 As spending rises, deficits and debt will increase. Debt held by the public is expected to soar from 78 percent of GDP today to 123 percent by 2040.

Our fiscal path will be even more troubling than the CBO is projecting if:

- Policymakers continue to break discretionary spending caps.

- The United States faces unforeseen wars and military challenges.

- The economy has another deep recession.

- Future presidents and congresses launch new spending programs.

- Interest rates are higher than projected, raising interest costs further.

Given these possible scenarios, the administration’s efforts to improve agency efficiencies and cut low-value programs and activities is greatly needed.

As the size of the government has grown over the decades, so has the scope of its activities. The federal government funds about 2,300 aid and benefit programs today, more than twice as many as in the 1980s.3 The federal budget has grown too large for Congress to adequately monitor or review. Consider, for example, that the federal budget at $4 trillion is 100 times larger than the budget of the average U.S. state of about $40 billion.

All 2,300 programs are susceptible to management and performance problems. Because the government is so large, problems may fester within agencies for years without Congress taking notice or action. The management breakdowns leading to the scandals at the Secret Service and Department of Veterans Affairs are examples. Furthermore, the more activities in society that the federal government intervenes in, the less time Congress has to focus on core federal responsibilities such as national defense.

For these reasons, the OMB-led effort to identify programs to eliminate and consolidate makes a lot of sense. The government will never operate as efficiently as a private business, but it would perform better with fewer failures if it were much smaller. When it comes to the federal government, less is more.

Where to Find Savings

When looking for savings in the federal budget, policymakers often look at particular departments to find savings, or particular categories such as mandatory and discretionary. Another way to look at the budget is to put all federal spending, other than interest, into four boxes: employee compensation, purchases (procurement), aid to the states, and benefit and subsidy programs. Figure 1 shows the share of total noninterest federal spending on each item.

Employee Compensation. Federal wages and benefits for 3.6 million federal employees accounts for 11 percent of noninterest spending. There are 2.1 million civilian workers and 1.5 million uniformed military.4 There are savings to be found in staffing levels and compensation. Federal benefits, such as pension benefits, are excessive compared to the private sector.5

Purchases (Procurement). This category accounts for 14 percent of noninterest spending. Budget experts have long criticized the inefficiencies of federal purchasing. Large cost overruns on major projects, for example, have long been a problem at the Pentagon and other agencies.6 A 2014 Government Accountability Office report noted, “Weapon systems acquisition has been on GAO’s high risk list since 1990 … While some progress has been made on this front, too often we report on the same kinds of problems today that we did over 20 years ago.”7 Another problem is poor management of the government’s bloated real property holdings of 275,000 buildings and 481,000 structures.

Aid to the States. The federal government funds more than 1,100 aid programs for the states, including programs for highways, transit, education, and other activities.8 Federal aid to the states totals more than $600 billion a year, and accounts for 17 percent of noninterest spending. The OMB memo directs agencies to consider federalism as a factor in their Agency Reform Plans, and to focus resources on activities where there is a “unique federal role.” Agencies should consider which current activities could be performed better by the states or the private sector.

Benefits and Subsidies. The largest portion of federal spending—at 58 percent—is payments to individuals and businesses in benefit and subsidy programs, such as Medicare and farm aid. Management reforms could save money by cutting fraud, abuse, and erroneous payments to individuals and businesses. More important, policymakers should scrutinize every benefit and subsidy program with respect to OMB’s criteria of federalism and cost-benefit analysis.

Agency Reform Plans (ARPs)

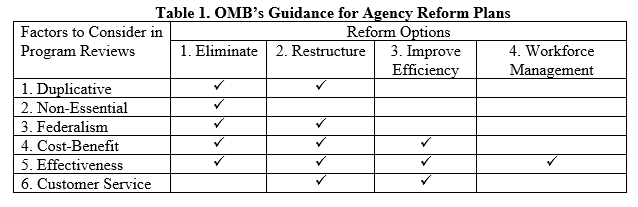

The OMB memo discusses factors for agencies to consider in assembling their ARPs, and it discusses reform options for failing programs. Table 1 summarizes the OMB’s six proposed factors and four reform options.

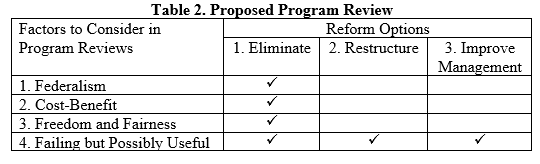

The OMB analysis is fine as far as it goes, but I would suggest a simpler review matrix for federal programs, as shown in Table 2. The table includes OMB’s criteria for federalism and cost-benefit, but suggests two new review criteria.

To reform the government, Congress and agencies should review programs and activities with an eye to the four factors in Table 2, which are discussed in the following sections.

Federalism: Under the Constitution, the federal government was assigned specific limited powers, and most government functions were left to the states. But federalism has been increasingly discarded as the federal budget has grown. Through grant-in-aid programs, Congress has undertaken many activities that were traditionally reserved to state and local governments. Grant programs are subsidies combined with regulatory controls that micromanage state and local affairs.9 Federal aid to the states totals more than $600 billion a year.

The OMB memo directs agencies to consider federalism as a factor in their ARPs. It asks agencies to consider whether each program could be better handled by state and local governments or the private sector. In my view, for most aid programs, the answer is yes.

Federal aid has many disadvantages. It encourages overspending by the states. The aid shares allotted to each state do not necessarily match need. The regulations tied to aid programs reduce state policy freedom and diversity. Aid breeds bureaucracy as multiple levels of government must handle the paperwork. Aid programs distract federal policymakers from national concerns such as defense. And aid programs make political responsibilities unclear—they confuse citizens about who is in charge.

The federal aid system is a roundabout way to fund state and local activities, and it should be downsized. So the OMB is on the right track asking agencies to look for activities to eliminate that are not properly federal in nature.

Cost-Benefit Analysis. The OMB memo asks agencies to evaluate whether the costs of agencies and programs are justified by the benefits they provide. Cost-benefit analysis is a standard tool of economics that could give decisionmakers in agencies and Congress better information about the overall value of programs.10

Since 1981, federal agencies have been required to perform such analyses for major regulatory actions.11 However, there is no general requirement for federal agencies to perform cost-benefit analysis for spending programs. The scorekeeper of Congress, the CBO, generally does not perform them either. Some agencies perform cost-benefit analyses for some programs and projects, but there is no mandate to do so for most programs.

Thorough cost-benefit analyses would take into account the full costs of funding programs, including the direct tax costs and the “deadweight losses” of taxes on the economy. Deadweight losses stem from changes in working and other productive activities that occur when taxes are extracted from the private sector. Economic studies of income taxes have found, on average, that the deadweight loss of raising taxes by one dollar is about 50 cents.12

Suppose that Congress is considering spending $10 billion on an energy subsidy program. Does the program make economic sense? The program’s benefits would have to be higher than the total cost on the private sector of about $15 billion, which includes the $10 billion direct taxpayer cost plus another $5 billion in deadweight losses. OMB Circular A-94 establishes guidelines for federal cost-benefit analyses, and it suggests agencies use a deadweight loss value of 25 cents on the dollar.13

The 2018 federal budget includes a chapter on using data and research to improve government effectiveness.14 And in September, a congressional commission released a major report on evidence-based policymaking.15 The report focused on generating better data for program evaluations, but had less to say about how to increase the government’s use of evaluations to eliminate low-value programs. More program evaluations are needed, and they should be better integrated into the actual decisionmaking of agencies and Congress.

Policymakers should require agencies to evaluate more of their programs with full cost-benefit analyses and to release the results. There can be substantial disagreement about the results of such studies, but the process is useful because it requires the government to at least try to quantify the merits of its policy actions. Without considering the full costs of programs, including deadweight losses, policymakers are biased toward supporting programs that do not generate net value.

That said, evaluating programs with cost-benefit analysis is a secondary concern compared to issues of constitutional federalism and defending individual freedom against government encroachment. It is also true that, effective or not, spending programs need to be downsized if we are to ward off the federal debt crisis that is projected in the years ahead.

Freedom and Fairness

The OMB memo lays out criteria for evaluating programs based on practical and economic considerations. However, there are also qualitative criteria—such as fairness and personal freedom—that federal officials and members of Congress should always consider when evaluating programs. For one thing, federal programs and activities should not abridge fundamental rights, such as free speech rights. In that area, the IRS targeting scandal illustrated why we need rigorous oversight of agencies, especially agencies handed exceptional powers.

In reviewing programs, policymakers should consider broad freedom issues, such as personal privacy. As an example, policymakers should be skeptical of programs and activities that require the collection of substantial amounts of personal data on Americans. In this age of computer hacking, such activities create threats if agency protections break down, as they often do.

In his 1962 book, Capitalism and Freedom, economist Milton Friedman talked about the costs and benefits of government action. He said that in evaluating policies, we should always count the cost of “threatening freedom, and give this effect considerable weight.”16 While “the great advantage of the market … is that it permits wide diversity,” he said, “the characteristic feature of action through political channels is that it tends to require or enforce substantial conformity.”17 The individual mandate under the Affordable Care Act is the sort of freedom violation that expansive government results in.

Programs that violate our personal freedoms are morally wrong, but they also tend to be impractical.18 As Friedman noted, policies fail when they “seek through government to force people to act against their own immediate interests in order to promote a supposedly general interest.”19 Economist Thomas Sowell noted similarly that supporters of government mandates seem to think “people can be made better off by reducing their options.”20 Rather than making people better off, government mandates and interventions often lead to social conflict.

Another qualitative aspect of federal programs to consider is fairness. Of course, that word has a loose meaning, and the political left and right often disagree about the fairness of particular programs. However, nearly everyone would agree that equality before the law should be considered when reviewing federal activities. And many Americans of all political stripes would agree that programs which hand out subsidies to businesses and the wealthy are dubious. Thus, even if such programs are run efficiently, the government should not be running them at all.

Failing but Possibly Useful

The OMB memo says that there is “growing citizen dissatisfaction with the cost and performance of the federal government.” That is true.21 Only one-third of Americans think that the federal government gives competent service, and, on average, people think that more than half of the tax dollars sent to Washington are wasted.22 The public’s “customer satisfaction” with federal services is lower than their satisfaction with virtually all private services.23

In his book, Why Government Fails So Often, Yale University’s Peter Schuck concluded that federal performance has been “dismal,” and that failure is “endemic.”24 In a 2014 study, Paul Light of the Brookings Institution found that the number of major federal government failures has increased in recent decades.25

Some agencies and programs are performing poorly, but they are important federal functions, and so they should be overhauled to fix problems. Repeated Secret Service failures, for example, have led to calls to restructure that agency.26 Improving federal management is an ongoing challenge, and it is more difficult the larger the government grows.

There are basic structural reasons why the federal government will always be less efficient than the private sector.27 Federal agencies do not have the goal of earning profits, so they have little reason to restrain costs or improve service quality. And unlike businesses, poorly performing programs do not go bankrupt. If program costs rise and quality falls, there are no automatic correctives. By contrast, businesses abandon activities that are failing, and about 10 percent of all U.S. companies go out of business each year.28

There are other causes of poor federal management. Government output is difficult to measure, and the missions of federal agencies are often vague and multifaceted making it hard to hold officials accountable. Federal programs are loaded with rules and regulations, which reduces operational efficiency. One reason for all the rules is to prevent fraud and corruption, which are concerns because the government hands out so much money.

All that said, there are ways to reduce federal bureaucracy and improve agency incentives. Research has found that American businesses have become leaner in recent decades, with flatter managements.29 By contrast, the number of layers of federal management has increased. Paul Light found that the number of management layers in a typical federal agency has more than doubled since the 1960s, and he believes that this is one cause of federal failure today.30 So reducing management layers in agencies should be a goal for the OMB to emphasize.

Congress should reform federal compensation. One issue is that employee pay is mainly based on standardized scales generally tied to longevity, not performance. The rigid pay structure makes it hard to encourage improved work efforts, and it reduces morale among the best workers because they see the poor workers being rewarded equally.

Congress should make it easier to discipline and fire poorly performing federal workers. When surveyed, federal employees themselves say that their agencies do a poor job of disciplining poor performers.31 Govexec.com noted, “There is near-universal recognition that agencies have a problem getting rid of subpar employees.”32 Just 0.5 percent of federal civilian workers get fired each year, which is just one-sixth the private-sector firing rate.33

In sum, OMB efforts to reform the federal workforce and improve agency management are greatly needed. However, there are limits to how much federal management can be improved. The government has simply become too large to manage effectively, and many of its activities could be better performed by the states and private sector. As such, legislative action to eliminate agencies and programs is more important than just making agencies work more efficiently.

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

Notes:

1 Office of Management and Budget, “Comprehensive Plan for Reforming the Federal Government and Reducing the Federal Civilian Workforce,” M-17-22, April 12, 2017. The memo followed from Executive Order 13781 issued March 13, 2017.

2 Congressional Budget Office, “The 2017 Long-Term Budget Outlook,” March 2017.

3 Chris Edwards, “Independence in 1776; Dependence in 2014,” Cato at Liberty, Cato Institute, July 3, 2014. The current federal program count is available at www.cfda.gov.

4 Bureau of Economic Analysis data. Excludes the U.S. Postal Service.

5 Chris Edwards, “Reducing the Costs of Federal Worker Pay and Benefits,” DownsizingGovernment.org, Cato Institute, September 20, 2016.

6 Chris Edwards and Nicole Kaeding, “Federal Government Cost Overruns,” DownsizingGovernment.org, Cato Institute, September 1, 2015.

7 Government Accountability Office, “Defense Acquisitions,” GAO-14-563T, April 30, 2014, p. 1.

8 Federal aid programs are discussed in Chris Edwards, “Fiscal Federalism,” DownsizingGovernment.org, Cato Institute, June 2013.

9 Federal aid programs are discussed in Chris Edwards, “Fiscal Federalism,” DownsizingGovernment.org, Cato Institute, June 2013. And see Chris Edwards, “Federal Aid to the States: Historical Cause of Government Growth and Bureaucracy,” Cato Institute, May 22, 2007.

10 Most public finance textbooks provide background on cost-benefit analysis. See David N. Hyman, Public Finance: A Contemporary Application of Theory to Policy (Mason, Ohio: Thomson South-Western, 2005), Chapter 6. Or see Harvey S. Rosen, Public Finance: Sixth Edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), Chapter 11.

11 President Reagan issued Executive Order 12291 in 1981 mandating the use of cost-benefit analysis for significant regulatory actions, which are those that have an impact of more than $100 million a year. The order was superseded by President Clinton’s Executive Order 12866 in 1993. “Independent” federal agencies are exempt from the requirements. For background, see Susan E. Dudley, Testimony to the Joint Economic Committee, “Reducing Unnecessary and Costly Red Tape through Smarter Regulations,” June 26, 2013. And see Robert W. Hahn and Erin M. Layburn, “Tracking the Value of Regulation,” Regulation 26, no. 3 (Fall 2003).

12 Chris Conover surveyed the literature and reported an average of 44 cents for the marginal cost of all federal taxes, and 50 cents for federal income taxes. Christopher J. Conover, “Congress Should Account for the Excess Burden of Taxation,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 669, October 13, 2010. See also Edgar K. Browning, Stealing From Ourselves: How the Welfare State Robs Americans of Money and Spirit (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2008), pp. 156, 166, 178. The Congressional Budget Office has stated, “Typical estimates of the economic cost of a dollar of tax revenue range from 20 cents to 60 cents over and above the revenue raised.” Congressional Budget Office, “Budget Options,” February 2001, p. 381.

13 Deadweight losses are also referred to as excess burdens. Office of Management and Budget, “Circular No. A-94 Revised,” October 29, 1992. A review by the author of a small sample of cost-benefit analyses of federal programs found that none included the deadweight losses of taxes. As an example, Mathematica did a 98-page analysis of Job Corps on contract to the Department of Labor in 2006. It found that the benefits of the program were $3,544 per participant, while the costs were $13,844, for a net loss of $10,300 per participant. The inclusion of deadweight losses would have made the losses higher. See Peter Z. Schochet, John Burghardt, Sheena McConnell, “National Job Corps Study and Longer-Term Follow-Up Study,” Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., August 2006.

14 Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018, Analytical Perspectives (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2017), Chapter 6.

15 Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, “The Promise of Evidence-Based Policymaking,” September 2017, www.cep.gov/content/dam/cep/report/cep-final-report.pdf.

16 Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), p. 32.

17 Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), p. 15.

18 The relationship between government force and program failure is explored in Chris Edwards, “Why the Federal Government Fails,” Cato Institute, July 27, 2015.

19 Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), p. 200.

20 Thomas Sowell, Knowledge and Decisions (New York: Basic Books, 1980), p. 173.

21 After his examination of polling data, Yale University law professor Peter Schuck concluded, “the public views the federal government as a chronically clumsy, ineffectual, bloated giant that cannot be counted upon to do the right thing, much less do it well.” Peter H. Schuck, Why Government Fails So Often (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), p. 4.

22 John Samples and Emily Ekins, “Public Attitudes toward Federalism,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 759, September 23, 2014, Figures 24 and 27.

23 American Customer Satisfaction Index, “ASCI Federal Government Report 2014,” January 27, 2015, www.theacsi.org.

24 Peter H. Schuck, Why Government Fails So Often (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), pp. 371, 372.

25 Paul C. Light “A Cascade of Failures,” Brookings Institution, July 2014, p. 1.

26 Louis Nelson, “Chaffetz: Secret Service reforms possible after latest fence jumping incident,” Politico, March 20, 2017.

27 Chris Edwards, “Bureaucratic Failure in the Federal Government,” DownsizingGovernment.org, Cato Institute, September 1, 2015.

28 Brian Headd, Alfred Nucci, and Richard Boden, “What Matters More: Business Exit Rates or Business Survival Rates?” BDS Brief 4, U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2010.

29 Raghuram Rajan and Julie Wulf, “The Flattening of the Firm,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 9633, April 2003.

30 Paul C. Light “A Cascade of Failures,” Brookings Institution, July 2014, p. 11. And see Paul C. Light, “Perp Walks and the Broken Bureaucracy,” op-ed, Wall Street Journal, April 26, 2012.

31 Paul Light’s research cited in Peter H. Schuck, Why Government Fails So Often (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), p. 322.

32 Eric Katz, “Firing Line,” Government Executive, January–February 2015.

33 Andy Medici, “Federal Employee Firings Hit Record Low in 2014,” www.federaltimes.com, February 24, 2015. And see Chris Edwards, “Federal Firing Rate by Department,” Cato Institute, June 6, 2014.